Saturday, November 6, 2010

JAPANESE FILM BLOGATHON: The Fall and Rise of Seijun Suzuki: Part 2

The Toronto J-Film Pow-Wow is proud to post the second half of the second half of our article "The Fall and Rise of Seijun Suzuki" as part of this year's Japanese Film Blogathon. To read the first half please click here.

by Chris MaGee

It's usually this period in Seijun Suzuki's career, the 12 years between his firing from Nikkatsu for "Branded to Kill" and the release of "Zigeunerwesien", that tends to get glossed over. The way most people discuss these years one could easily get the feeling that Suzuki was hiding in seclusion and barely able to eke out a living. This wasn't really the case. During the time of his lawsuit against Nikkatsu Suzuki was actually quite prolific.Without his regular studio income he made ends meet by directing a trio of TV projects. The first of these came only four months after his firing from Nikkatsu. In August 1968 Suzuki directed an episode of the TBS series "Good Evening Dear Husband" titled "A Duel". That was followed up the next year with an episode of the NTV series "Kurobe's Sun" titled "There's a Bird Inside a Man". Finally in 1973 Suzuki was asked to direct the premiere episode of the "Twilight Zone"-esque Fuji TV series "Horror Theatre Unbalance". This episode titled "A Mummy's Love", an adaptation of a macabre short story by author Fumiko Enchi, reunited him with two of the members of his Nikkatsu "Group of Eight", Atsushi Yamatoya and Yozo Tanaka. It's interesting to note that "Horror Theatre Unbalance" became a bit of a haven for directors who either worked on the margins of the Japanese film industry, like New Wave filmmaker Kazuo Kuroki, or for those who had jumped ship at Nikkatsu, like Yasuharu Hasebe who found the studio's decision to move into the production of Roman Porno, "romantic pornography" to be in poor taste. Even in this television sweet spot though Suzuki, the self-professed mischief maker, still managed to piss people off. Nissan Motors, one of the major sponsors of "Kurobe's Sun" pulled their commercials from Suzuki's episode because of an "objectionable scene in which the hero is hit by a car."

Despite his lawsuit with Nikkatsu dragging on (and the annoyance that he engendered with the ad execs at Nissan) Suzuki was doing relatively well. With the money from these TV projects coupled with the eventual settlement paid out by Nikkatsu he could get through the next few years by picking up the occasional job directing TV commercials. The rest of the time he wrote essays that were compiled into a book named after his 1966 film "Kenga Erejii (Fighting Elegy)" plus he continued active friendships with his old cohorts Takeo Kimura, Atsushi Yamatoya and Yozo Tanaka. Tanaka actually was a neighbour of Suzuki and the two men would often meet at Suzuki's home for games of Go and long discussions of how to make a new kind of film, one that used the avant-garde territory of "Branded to Kill" as a jumping off point. Suzuki would keep these long chats in mind as he waited for the day when he hoped he'd be allowed to return to feature filmmaking. In the meantime though Tanaka and Atsushi Yamatoya were working on a project, one that took its inspiration from "Branded to Kill". It was also one that would eventually lead to the triumphant return of Seijun Suzuki.

Both Atsushi Yamatoya and Yozo Tanaka had both had writing credits on "Branded to Kill", in fact Yamatoya had starred in the film as Killer No. 4 Koh. It was during the writing of the film that Yamatoya and Tanaka came up with the idea of a loose sequel to "Branded to Kill", one that would follow the character of the No. 1 Killer as he fights against the other members of the secret society of assassins. These would include quite a few sexy half-clad female killers. At first Yamatoya tried to write the screenplay himself, but his docket was already full writing scripts for films like Chusei Sone's "Showa Woman: Naked Rashomon", Yasuharu Hasebe's "Stray Cat Rock: Sex Hunter" and Toshiya Fujita's "Sweet Scent of Eros", so the task of finishing the screenplay was taken up by Tanaka. Once that was done though the two men were left with the dilemma of finding some kind of financing for the film. It would be folly to go knocking on doors at Nikkatsu. Having lost their legal fight with Suzuki the last thing they wanted was another "Branded to Kill" on their hands. Ultimately Yamatoya had to mine his contacts in Tokyo's underground film and theatre scene to somehow get his project made. Yamatoya had plenty of connections in the avant-garde having co-written scripts with writer/ director/ leftist radical Masao Adachi for 1966's "Season of Betrayal" and 1971's "Gushing Prayer" (the latter under the pseudonym Wataru Hino), so taking a walk on the artistic wild side wouldn't be a problem. His connections paid off, because here he and Tanaka met Genjiro Arato.

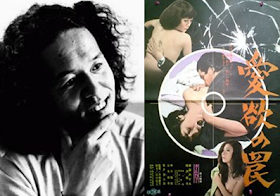

Arato was the director of his own underground theatre troupe called Tenshogikan, "The Planetarium Hall". At that point in the early 1970's Tokyo was alive with these troupes that the Japanese referred to as shogeki, literally "small theatre". Tenjo Sajiki, Sakura, Tsuji Pro, Transformation, and more - dozens of these fringe troupes had been established in the city since the mid-1960's. Fueled by the public outrage against the U.S.-Japan Mutual Security Treaty, popularly known as ANPO, and taking their inspiration from the works of Jean Genet, Jean-Paul Sartre, Antonin Artaud, as well as avant-garde "happenings" the shogeki were out to topple traditional Japanese theatre and shock the establishment. What better place for rebellious spirits like Yamatoya and Tanaka to find funding and talent than amongst other rebels? Arato agreed to not only take the lead role of the No. 1 Killer, but he also offered the services of the actors and actresses in Tenshogikan. What's best is that with Yamatoya directing Arato was also convinced to finance the production with his own money. The truly unbelievable feat though was that upon the film's completion Yamatoya got it distributed by Suzuki's nemesis Nikkatsu. There was enough naked female flesh in the film that the studio released it on December 15th, 1973 as part of their Roman Porno line under the title "Trap of Lust". While the release of "Trap of Lust" wouldn't at that time benefit Seijun Suzuki directly it would put him just one degree of separation between himself and Genjiro Arato. In the world of film its these tangential relationship that can make or break a director, especially when they have the kind of spectacular failure that Suzuki was about to endure.

In 1977 the day that Suzuki had been waiting for seemed to have arrived. Atsushi Yamatoya had penned a screenplay based on a story idea by manga artist Ikki Kajiwara about a fashion model who is transformed by a handsome trainer into a golf pro. Kajiwara had come to fame after writing a manga for Weekly Shōnen Magazine under the pseudonym Asao Takamori. "Ashita no Joe", the story of an orphaned streetfighter who becomes a lightweight boxing contender had captured the imagination of an entire generation of young Japanese. During the late 60's and early 70's "Ashita no Joe" had been embraced by student protesters, and even members of the radical leftist Red Army, as a near patron saint. Shochiku was willing to bank roll this Kajiwara/ Yamatoya script titled "A Story of Sorrow and Sadness" if Kajiwara was to produce. Meanwhile Yamatoya convinced a cagey Shochiku to bring his old friend Seijun Suzuki to come on board to direct. At that point in the late 70's the normally conservative, family-minded Shochiku had been mining talent from the margins of film and theatre for its productions. The hiring of experimental filmmaker Nobuhiko Obayashi for Shochiku's psychedelic 1978 horror film "House" was a good example of this. Seijun Suzuki, who had been spending the better part of the last nine years mulling over how he could create a new kind of film, wasn't ready to make a standard sport underdog movie though. With actress Yoko Shiraki and Yoshio Harada in the leads Suzuki turned "A Story of Sorrow and Sadness" into a fever dream meditation on the dehumanizing effects of fame. Using some truly stinging symbolism and gleefully disregarding continuity the film can be counted alongside "Tokyo Drifter", "Branded to Kill" and "Zigeunerweisen" as one of Suzuki's best works. Still audiences, at least the audiences that Shochiku was trying to appeal to, weren't looking for more than a feel good sports story with a pretty girl. A statement from the review for "Branded to Kill" that appeared in the June issue of the Eiga Geijutsu film journal could just as easily apply to "A Story of Sorrow and Sadness" - "We do not go to theatres to be puzzled." Seijun Suzuki's return to feature filmmaking promptly bombed.

In the wake of this failure many people, both in the Japanese film industry and without, would have agreed with Nikkatsu president Kyusaku Hori and said that "Suzuki should open a noodle shop," but Suzuki himself refused to give up. The only thing that he had ever done was make films, so that's what he continued to do. In 1979 he picked up another TV job, an episode of Fuji TV's "Sunday Horror Series" written by Atsushi Yamatoya. Titled "The Fang in the Hole" it starred actress Naoko Inagawa as a woman haunted by her dead gangster boyfriend (portrayed by Yoshio Harada). Although shot on a shoestring budget "The Fang in the Hole" showed that Suzuki hadn't lost his confidence as a filmmaker. The feeling of the episode picks up where "A Story of Sorrow and Sadness" left off. Stark, brilliantly coloured sets contrasted with wildly theatrical staging. Given the freedom to produce work like this Suzuki could have easily kept innovating in the world of television, but he and Yozo Tanaka had other ideas. Both friends had been working on a script based on the 1951 novel "Disk of Sarasate" by novelist Hyakken Uchida. Uchida had enjoyed his greatest popularity during the Taisho Era (1912-1926), a period in Japan's history that rolled America's Roaring 20's and the decadence of Weimar Germany into one. It was a period that fascinated Suzuki, in part because he was born at the tail end of it in 1923. Not wanting to start checking out real estate for that noodle shop Suzuki and Tanaka started looking for ways to fund their script, titled "Zigeunerweisen" (German for "Gypsy Airs"), without the help of a major studio. Tanaka remembered the the assistance he and Atsushi Yamatoya had received from Genjiro Arato with "Trap of Lust", so that's the door that he and Suzuki knocked on. Luckily for them Arato was in a generous mood.

Seijun Suzuki had lucked out. Just like he had done with "Trap of Lust" Genjiro Arato agreed to finance and produce "Zigeunerweisen". A little digging in his past reveals why Arato may have been so sympathetic to Suzuki's plight. When Arato was only in his early 20's he'd suffered through a painful firing as well. Before he had founded Tenshogikan Arato had been an actor in the most influential shogeki theatre troupe, Jokyo Gekijo, "The Situation Theatre". Founded in 1964 by writer and actor Juro Kara it had been named after a play by existentialist author and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, but soon that name was replaced in peoples minds by a new one - The Red Tent. This was because Jokyo Gekijo didn't hold their performances in traditional theatres. Like many shogeki troupes they took their performances off the stage and into the streets, or in the case of Jokyo Gekijo into the park. It was in various public parks that the troupe would erect their theatre, a red tent. Performances were only announced hours before they were to begin, both as a way to build excitement and also to prevent the police from knowing where they'd appear next. Arato's time in the Jokyo Gekijo would influence the rest of his artistic career, but this time was short-lived. Only after 10 months in the troupe he was fired due to what Juro Kara felt were violent outbursts against three other troupe members during one of their plays. Arato had created his own second chance in the theatre by founding Tenshogikan in 1972, and now he was going to give Seijun Suzuki his second by putting up the money for "Zigeunerweisen".

With financing in place Suzuki began assembling his cast. "Lady Snowblood" and "Stray Cat Rock" director Toshiya Fujita would star as German professor Toyojiro Aochi, Yoshio Harada would star as Aochi's homocidal friend Nakasono, actress Naoko Otani would play dual roles as the gesiha Koine and Aochi's wife Sono, and actress Michiyo Ookusa would star as Aochi's perverse sister Shuko. A special appearance would be made by Jokyo Gekijo founding member and famed butoh dancer Akaji Maro as the blind beggar. In order to keep costs down nearly all of "Zigeunerweisen" was shot on location in Kamakura with locations being madly spliced and contrasted by Suzuki. Once again Takeo Kimura would provide the film's art direction. If the TV episodes that he'd worked on and "A Story of Sorrow and Sadness" were practice runs of Suzuki's new vision of film then "Zigeunerweisen" was his Suzuki's grand performance. While the story of the love/ hate friendship between Aochi and Nakasono and their swapping of lovers progresses in a fairly linear manner throughout the film's 145-minute running time Suzuki continually adds surreal flourishes - a giant red crab appears out of a dead woman's vagina, three blind beggars sing bawdy folk songs, characters who die mid-film continue to take part in the narrative. All this would definitely wow, or alienate, an audience, but once "Zigeunerweisen" was completed the question remained, how would an audience get to see it?

Seijun Suzuki had had a difficult enough time securing the directors job on "A Story of Sorrow and Sadness" at Shochiku and that film had bombed. With his bridges burned there and at Nikkatsu how was his latest film going to find a distributor? The studios themselves owned the theatre chains. The situation seemed impossible. That is until Genjiro Arato did what any good shogeki theatre director would do - he took "Zigeunerweisen" out of the studio run movie theatres and into the streets. Taking his cue from his Jokyo Gekijo days Arato had a special mobile, inflatable tent constructed and put up in Tokyo's Ueno Park. On April 1st, 1980 he began to hold regular screenings of "Zigeunerweisen" and something very strange began to happen. People came to see the film, and then they kept coming. Either a major shift had occurred in the Japanese consciousness since 1977, or Arato was simply smart enough to appeal to the arts crowd with his tent theatre. Regardless of the reason "Zigeunerweisen" ended up running for 22 weeks in its portable home, an estimated 56,000 tickets were sold and very quickly it began garnering glowing reviews. Once awards season rolled around Suzuki's film was honoured with trophy after trophy. It won Best Film, Best Director, Best Art Direction for Takeo Kimura and Best Supporting Actress for Michiyo Ookusa at the 1981 Japanese Academy Awards, plus it swept that year's Kinema Junpo Awards and had the honour of being named the Best Film of 1980 by the prestigious film journal.

No one could have predicted 12 years before that the dismissed and disgraced Seijun Suzuki would end up becoming one of the most honoured names in Japanese film. He ended up parlaying the success of "Zigeunerweisen" into two more films in what would become known as his Taisho Trilogy - 1981's "Kagero-za" and 1991's "Yumeji", both of which were produced by Genjiro Arato. What's even more satisfying is that "Branded to Kill", the film that nearly ended his career, has now become an undisputed classic of Japanese cinema. Suzuki even took the lead of Atsushi Yamatoya and Yozo Tanaka and made his own loose sequel/ remake of the film with 2001's "Pistol Opera". What is clear from Suzuki's success though is that it wasn't achieved by one single person. It was the result of longtime friendships, creative partnerships and the help from the world of Japan's avant-garde. Speaking of which, Genjiro Arato is still around too. In 2005 he produced the debut feature film of Tatsushi Omori, the son of Jokyo Gekijo alumni and "Zigeunerweisen" actor Akaji Maro. Titled "Whispering of the Gods" Arato once again screened the film in a tent theatre to avoid submitting the film to the Japanese censors. After the film finished its run he continued to screen films in the tent for several. First up, a retrospective of the work of "Group of Eight" member Atsushi Yamatoya including the "Branded to KIll" inspired "Trap of Lust".

No comments:

Post a Comment